I first became aware of Richard Llewellyn’s book, How Green was my Valley, in 1967, whilst living in Regina, Saskatchewan and was immediately impressed by how well he had captured life in the valleys, and particularly my home village, in the Rhymney Valley, Brithdir.

In 1970, I returned home and studied at University College, Cardiff, graduating with an Honours Degree in Mechanical Engineering. In the ensuing years and after many discussions over previous years with my family, I became intrigued by the similarities between my family history and those characters and events in the book.

I started with my great grandfather, Ebenezer Jones, who was not only a coal miner but periodically, would quit his job to go around the valleys bare knuckle fighting and carousing, until he got fed up and returned home to his family and a job in the mine, until my Great Grandmother, Mary Anne Jones, kicked him out. Eventually he died aged 57 years.

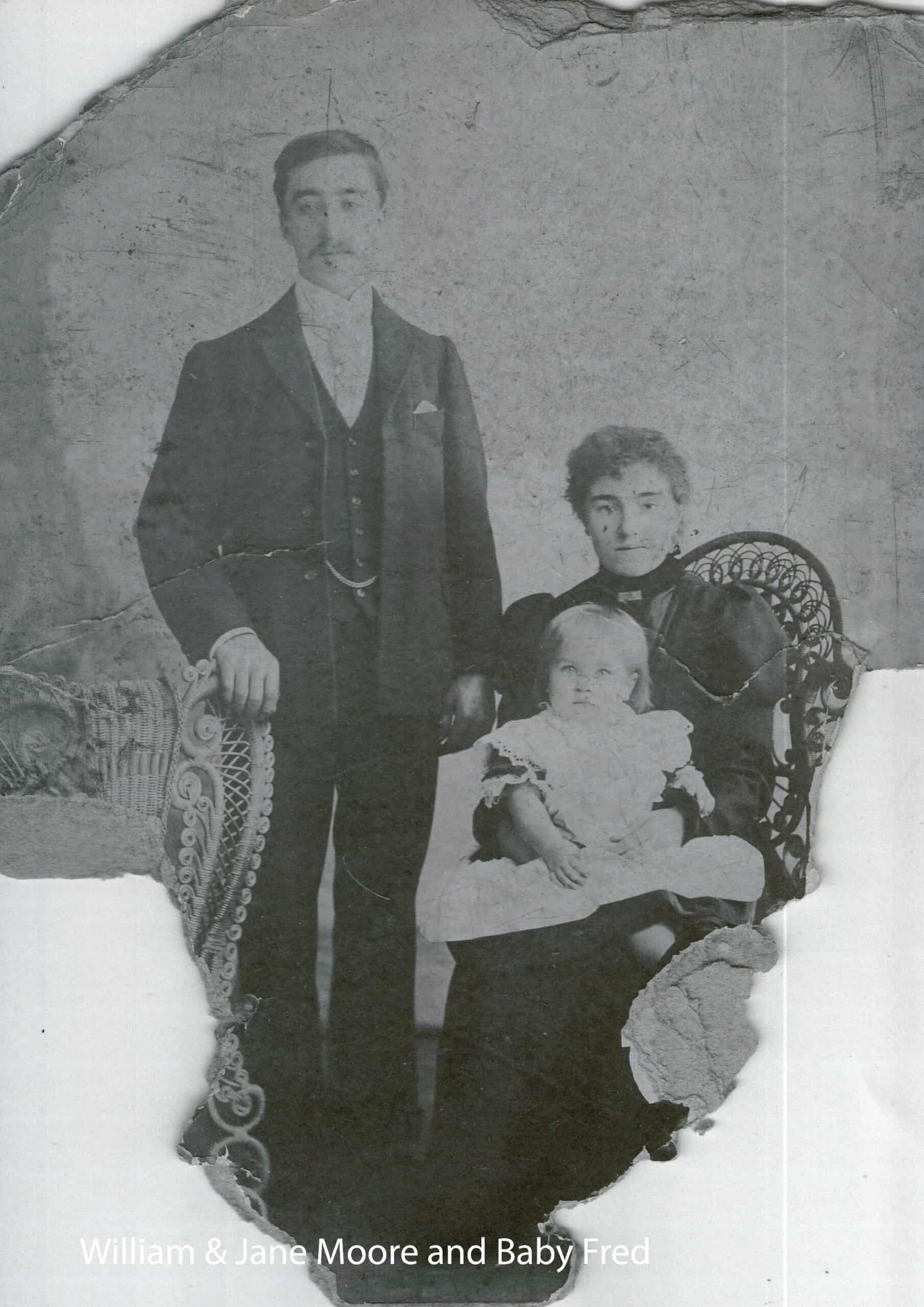

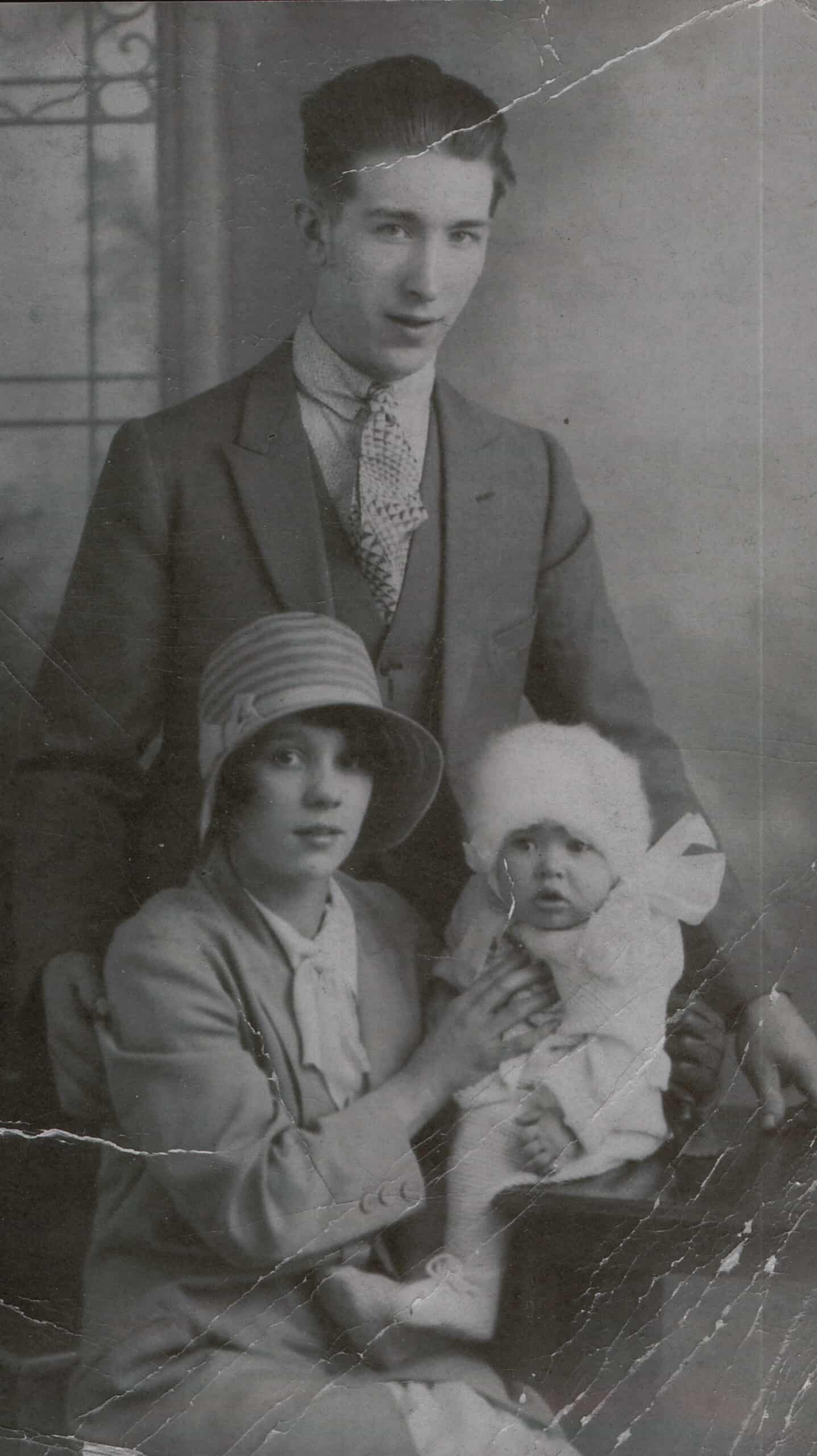

Six years later, Mary Anne bravely emigrated to the USA with her children, leaving my Grandmother, Jane Jones, age 17 years, to marry my Grandfather William Moore where they made their home in Brithdir for the rest of their lives.

I then remembered the discussions I had had with my Grandmother Jane about the time they left, and especially when she made her only visit to see her family, in Ohio, accompanied by her first born, Frederick.

When she returned with glowing memories of how wonderful the USA was, my Grandfather William told her that she should have stayed there and he would have followed.

But of course this was not to be.

Jane’s two brothers, Thomas and Noah Jones, also left the valley to find work in the USA.

Jane and William lived in No 22 Herbert Street, Brithdir, and went on to have 5 boys and 2 girls.

The two eldest boys worked in the mine and eventually my Uncle Thomas had an accident in the mine, as a result of which he died, leaving his wife and 3 children alone.

The third brother, Philip (pictured extreme left of the choir) was traumatised in the mine on his first day at work and decided to seek employment elsewhere but spent his spare time arranging music and performing with the village male voice choir.

Of the remaining two boys, one died soon after birth and the youngest, Kelvin, left the valley for good.

My mother, Enid, married Alfred Wells, son of William Wells, who lived in No 8 James Street, Brithdir.

Both men worked in the mine until that fateful day when my father had a conversation with his father at the coal face. My father turned and took a couple of steps away when he heard a crash behind him.

The ceiling at the coal face had collapsed killing his father instantly.

My mother told me that my Grandfather was brought home where she and my grandmother Wells washed him and dressed him in his best suite, before laying him out in the front room.

His father’s death caused Alfred to leave the mine and family to work in the Midlands never to return to the valley.

Among numerous other characters which interacted with the family were the Rev. Douglas Harris and Dr O’Shea who administered to Brithdir and surrounding area. Both men were close friends of the family.

Tommy Davies, the schoolteacher who caned me for misbehaving in class. He made me hold my hand out, palm uppermost, and brought the cane down very hard.

I was 7 years old and have never forgotten the pain he inflicted on me.

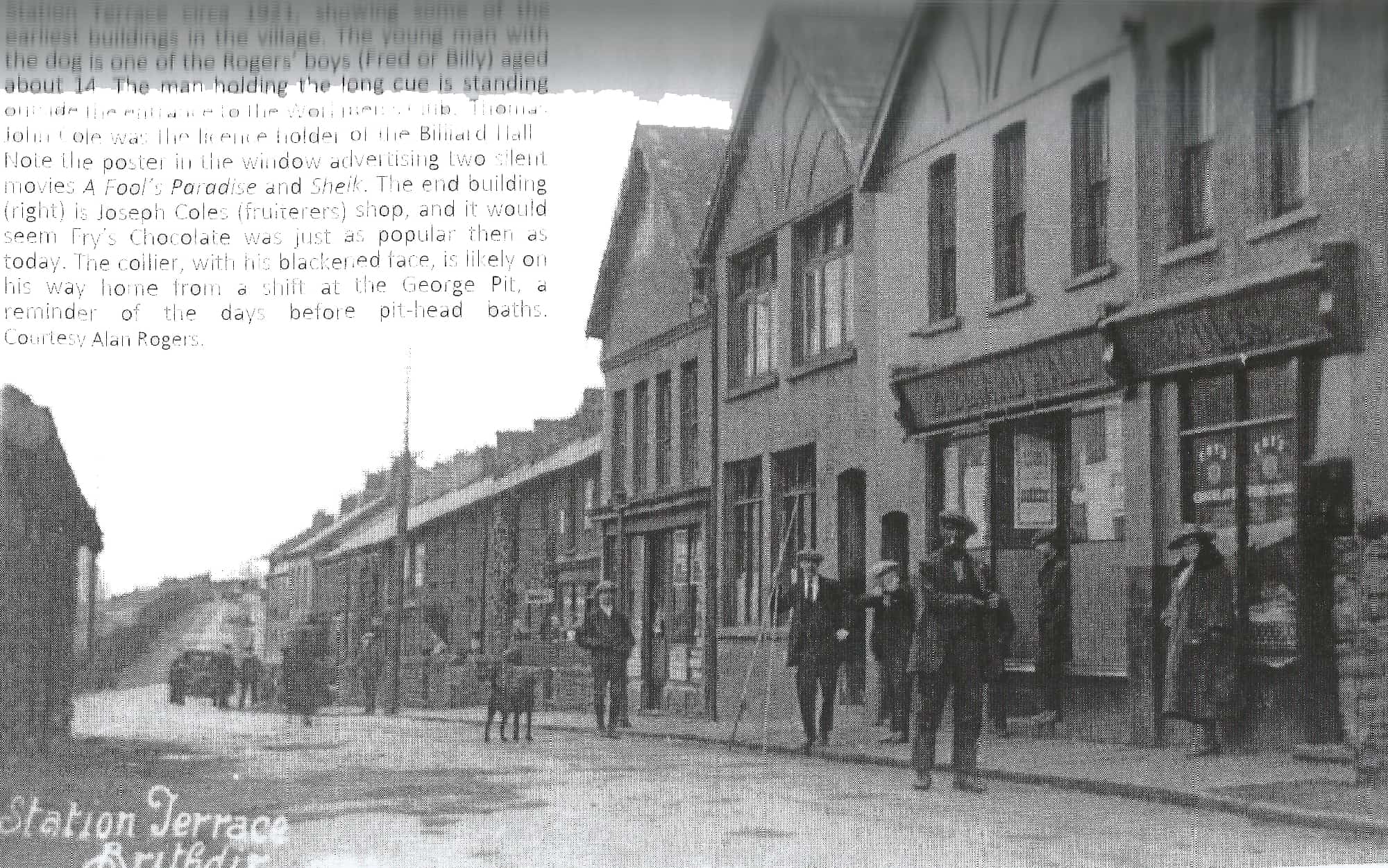

The Village of Brithdir during the period was created by the sinking of the George Pit coal mine, which is shown at the end of the row of houses named Station Terrace.

A miner, with his face, hands, and clothes, black with coal dust is seen walking home from his shift in the George Pit. These were the days before pit-head baths were provided.

Notice the total absence of safety helmets, overalls etc.

Miners had to wash in a tin bath in the kitchen with hot water provided by a coal fire helped by their wives and children.

They eventually received free coal which was delivered in one ton heaps and tipped in the street out side the front doors to their terraced houses. This meant that wives and families would have to first take up all rugs, fill buckets with coal and carry them through the house to the coal shed at the rear of the house. Large lumps would be carried separately to preserve their size as “small coal” Was more difficult to burn.

The women would then scrub the floors and replace the rugs etc.

My valley is now green again, but at what price?

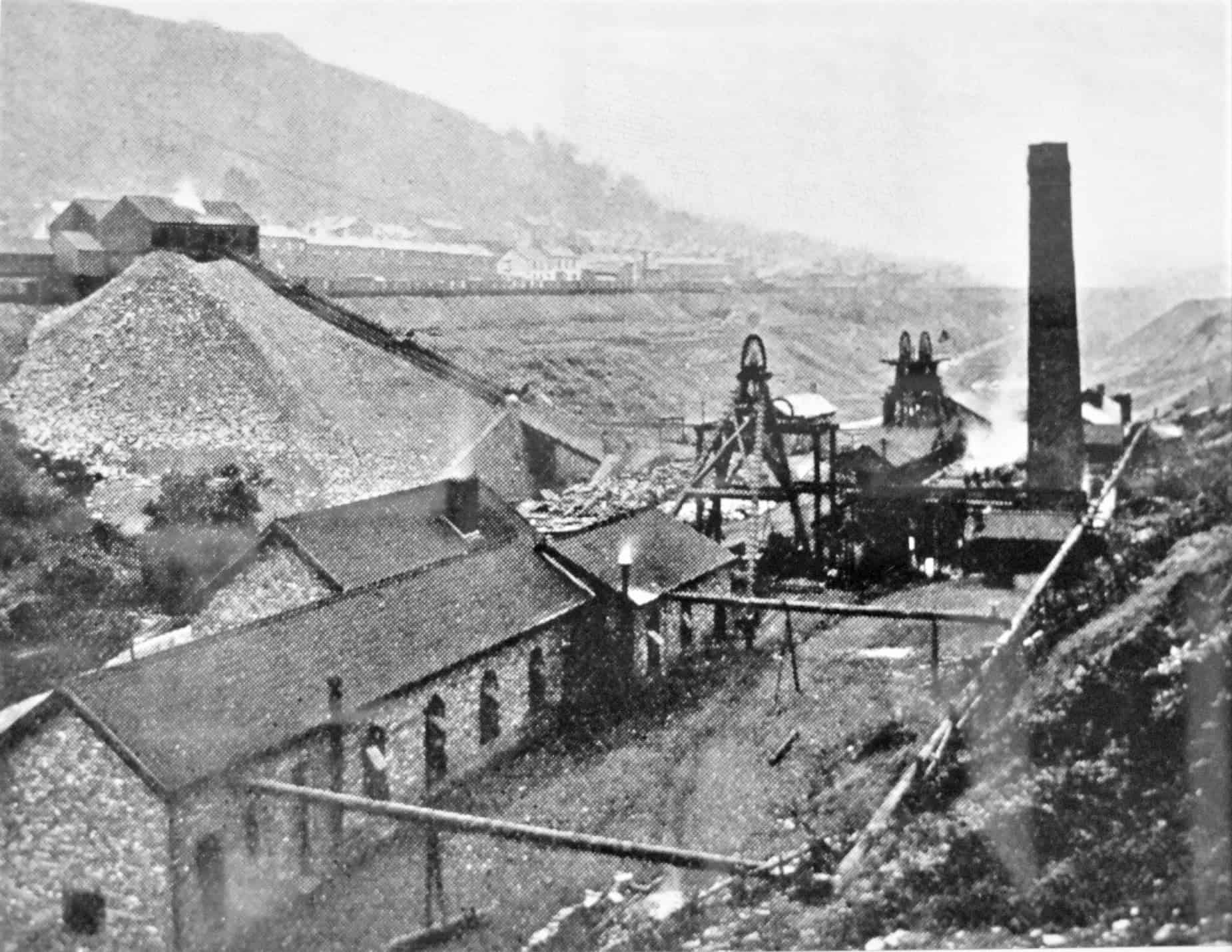

The Village of Brithdir during the period was created by the establishment of the George Pit coal mine which is shown at the end of the row of houses, Railway Terrace, and above the spoil tip of waste coal in the top left corner of the picture which shows also the mine named Coed y Moeth translation “Trees of Luxury”.

Both mines produced “house coal” from the Brithdir coal seam.

On the 25th May 1900 David James, a colliers assistant in Coed Y Moeth, was killed by a roof fall. He was 12 years old.

Not only was George Pit situated at the village but it can be seen that the waste coal tip polluted the Rhymney River such that its banks and water were just an oily sludge in which all wild life ceased.

Another mine, Elliot’s Mine, situated less than a mile away up the valley, deposited its waste coal by transporting it up the opposite hillside and formed a tip immediately above Brithdir on the top of the mountain at the top left corner in the photograph.

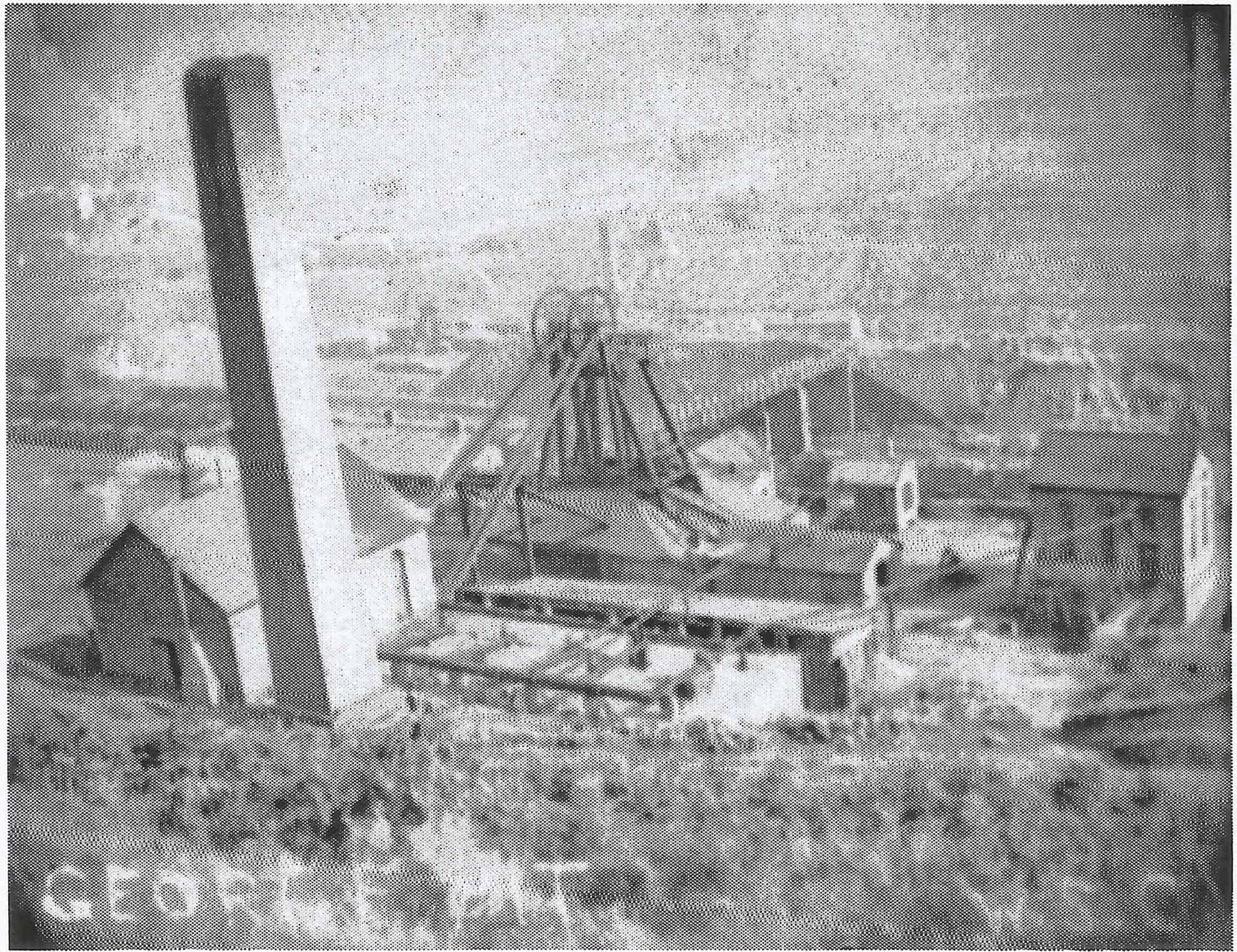

The village of Brithdir today still nestles between Bargod and Tirphil in the Rhymney valley. The site of George Pit, which was adjacent to the edge if the village, is now a children’s playground approximately 500 yards from the George Public house which remains.

The other mine, Coed y Moeth, which was situated just below the George pit at the side of the river, again within a few hundred yards of the village, has now gone without trace and the Elliots Colliery is now a museum but still retains part of the structure of the pit as an exhibit.

The waste coal tip has been removed from the top of the mountain but some of it which remains can be seen at the top of the photograph.

The Rhymney River now runs clear and has fish and other wildlife.

The chapel and church where we worshipped have been destroyed by fire and the unsightly structures carrying the overhead buckets, which fed the tip, have been removed.

The village itself still is as it was with its familiar back to back streets marching up and across the hillside bearing proudly the image associated with its heritage.

My valley is now green again, but at what price?

So this is the background to my story on which I and my associate Chris O’Hara have chosen to write as a musical.

I am aware that the storyline has similarities to Richard Llewellyn’s excellent novel. I have carried out extensive research into other productions over the past six plus years and been frustrated by the lack of response to numerous contacts made. Various productions of his story have been made but investigations have been proved fruitless.

Richard Llewellyn was mercilessly castigated by the media because he claimed that he had written his book based on his own experience in the mines of Wales when he had, as I understand it, written it as a result of researching the experiences of a Welsh family.

In my view he has captured the experiences of the thousands of Welsh mining families of the period.

I sincerely hope this musical will serve as a permanent memorial to those families who have suffered, and to all those who have died “mining the Coal” and will encourage people to read and appreciate Richard Llewellyn’s book of the same name.

The use of Coal as a fuel has been fundamental to the development and prosperity of the British Isles and other countries worldwide that have benefited and profited from the Industrial Revolution since its conception in 1740.